This is a sermon about dead baby boys. Maybe not what you

wanted here on the first Sunday after Christmas. In the Episcopal Church it’s

John chapter 1: in the beginning was the word and the word was with god and the

word was god. Cosmic and poetical and beautiful. And we have Herod killing baby

boys. A story that, scholars tell us, probably didn’t happen. Goodness, so why

read it? Why believe this stuff in the first place—that’s likely what some of

my new friends on campus would say. The Edge House has recently embarked on a

relationship with the Secular Student Alliance—atheists, agnostics, doubters,

they call themselves many things. But not Christian, not believers. “What

difference does this stuff make?” is a question they’re offering as a prompt

for an upcoming conversation. What difference does this stuff make? Particularly when it’s about dead babies?

I want to offer one possible answer, and it’s a bit

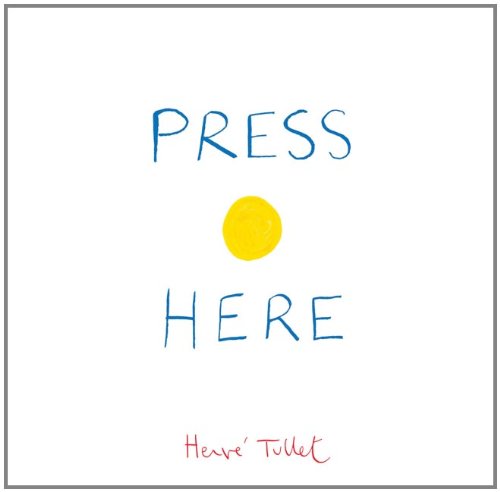

unorthodox. I want to read you a book. It’s called Press Here and it’s one of my 5-year-old daughter’s favorites. I want you to imagine we’re all

snuggled up in the bed—yes, all of us—and we’re all in our jim-jams and we’re

settled in to hear a story before bed. The book will be up on the screen, but

just pretend it’s right in front of you. Feel free to follow the directions.

[read book (2min, 40sec)]

I don’t know if Abby actually thinks pressing the colors

makes things happen, but she does it all the time. And she giggles…

Now, maybe there are a few folks out there who are thinking,

“yeah, that was cute, teaches kids cause and effect, but whatever, when’s

lunch?” Fair, I often think that during church… [grimace]

Only, here’s the funny thing: every adult who has picked it

up in my house and a few I’ve seen reading it in the bookstore, follow the directions and look up with a

big smile when they’re finished.

Every single one says something like “what a great book! I blew across the page

and the dots moved! I turned the lights on and off! Brilliant!”

I’m fairly certain that my adult friends don’t really think they caused those changes. The illustrator

painted those static images years ago, it doesn’t change on a second reading.

Come on.

This is a wonderful example of what theologian Marcus Borg

describes as the pre-critical, critical, and post-critical stages of faith development.

Pre-critical is basically us as kids: Stories about

Cinderella and Jesus and Batman and the President of the United States are all

equally truthful. Batman is an eccentric billionaire who became a superhero to

avenge his parents’ death—totally! And Jesus was born under a moving star and

magicians from the far East came to worship him--absolutely. They’re both

truthful and factual. And yes, there is a difference—facts generally show us

truth, but things that are true, deeply true that you feel in your gut,

sometimes aren’t factual. Think of you’re most favorite movie or novel that

changed how you see things in the world—true, maybe not factual.

Anyway, there’s nothing wrong with this stage except when we

get stuck in it—things we understand as meaningful have to be literally,

historically factual and we go to great lengths to make them so. Consider the seasonally-appropriate

film Polar Express and its take on

belief.

The critical stage is all about understanding the stories we

tell intellectually. How much of them are historically-accurate? Why did people

tell them? Were any of them codes for freedom like African-American spirituals

in the pre-Civil War South? Spoiler: yes, the books of Daniel and Revelation. Which

stories were several stories stitched together to make one like the story of

the great Flood in Genesis? What is the history of how we got the Hebrew

Scriptures and how were they edited over the centuries? In scholarly circles

this might be called the Historical-Critical Method and its main point is to

understand on a deeper level the Word passed down to us through the centuries

using historical resources outside of the Bible itself. They ask questions

about how different Hebrew or Greek words were used elsewhere or what events

were happening around the Jews that made them write different things. It’s good,

helpful stuff and pretty much all mainline denominations teach it in our

seminaries. But we can get stuck here as well.

Some theologians like John Shelby Spong go to great lengths

to disprove miracles and the more epic stories of the Bible, encouraging

believers to see the meaning behind the myths. But Spong and others lose the

poetry of scripture—it’s not just a list of dates and names but people’s lives

and their attempts to make sense of seeing God in action. If you “disprove”

that stuff, you lose much of the point. And many folks get so stuck in this

critical stage that God ceases to be real at all for them. If these events were

recorded and some invented by humans, where is the divine? It’s the reason so some

Christians push so hard against non-literal reading of scripture—folks think

that if any part of the Bible is not factual, it must not be true. And

therefore all of it is suspect. Again, not a good place to be stuck.

Luckily, Marcus Borg offers a third stage which many of us

dip in and out of when it comes to our faith.

The post-critical stage takes both the wide-eyed belief in the stories

as told and the scholarly, perhaps cynical understanding and holds them next to

one another at the same time. The story in Matthew about Jesus and his folks

fleeing to Egypt is a literary device to remind readers of both the Exodus led

by Moses and the later Exile when thousands were killed and displaced by

invading Babylon. There is no historical evidence and no other mention in the

Bible that Herod had any children killed, because of Jesus or not. But Matthew

recalls the prophet Jeremiah speaking of Rachel weeping over her children

Israel. Matthew is making past grief new again to make Jesus’ miraculous birth

and miraculous life even more miraculous. AND this story about a family

becoming refugees to avoid terrible death at the hands of a despotic leader is

deeply true. We have only to consider Syria and the 2,000,000 people, 1,000,000

of them children, who have fled the war there. Or mothers escaping abusive

relationships with their children. Or students fleeing a school-shooter.

Post-critical reading of scripture doesn’t take away from the beauty and

authority of the Word, it adds to it, deepens it. Like nostalgia or parenthood

adding flavor to the reading of Press

Here, even more do history, literary criticism, and our own

life-experiences add to the reading of scripture.

Now, there’s good news here beyond this lecture on how to

read scripture, I promise. It’s good news in itself that we don’t have to check

our brains at the door here,

BUT ALSO in the midst of this horrific account of the

slaughter of baby boys, Matthew recalls for us Jeremiah’s words, not only of

Rachel’s weeping for her children, but what follows: “Return, O virgin Israel,

return to these your cities. How long will you waver, O faithless daughter? For

the Lord has created a new thing on the earth: a woman encircles a man.

“God has created a new thing” is spoken by Jeremiah and

Isaiah and Matthew and John of Patmos in the book of Revelation. God is always

doing a new thing. And “By quoting this small bit…of Jeremiah,…Mathew…implies

the rest of the rest of it: it is Mary…being called back from exile, Mary, as

virgin Israel, that returns salvation to God’s people through the new thing on

earth which the Lord has done, through the man she encircles in her womb.”[1]

I just read a wonderful article in which a prostitute who is

also a junkie and a mom of 5 said, “you know what kept me through all that? God.

Whenever I got into the car, God got into the car with me.”[2]

how could we not draw parallels to school shootings or mass

graves in Sudan and WWII Germany? And we’re meant to. Herod’s evil, Babylon’s

evil, Pharoah’s evil are not unique nor is our mourning. We cry for our own

children—we cry when we lose them, we cry when they’re happy because the world

isn’t good enough for them, we cry because the same story seems to keep

happening. And then Jesus comes and, to the critical eye, the story is the same

and it doesn’t make any difference.

And to the post-critical eye, Jesus comes and there’s

something else going on. It’s the same story, but the themes are different,

it’s meaning is different, how we react to it is different.

It’s the same story, “A decree went out from Caesar Augustus

that all the world should be taxed…” and the no room at the inn, and the

shepherds, and the flight to Egypt to avoid the slaughter of the innocents.

It’s the same story, and with a post-critical eye, with the

eye that knows and embraces the traditional words and also knows how Matthew

has carefully crafted his account,

we see hope. We see that God is doing a new thing. God is

writing a new book and taking our crappy lives and memories and actions and

making something else, something unexpected with them.

There are people out there fighting against the world’s

brokenness and hurtfulness.

People inspired by Jesus and people who’ve never heard of

him.

People who will not just accept Herod and Babylon and

Pharoah.

May we be those people. May we see the hurt, may we stop and

ask if we can help. May we offer love in the place of judgment and embrace in

the place of fear.

[1]

excerpted from http://www.questionthetext.org/2013/12/23/mary-took-jesus-to-egypt-joseph-stayed-home/

, accessed 12/28/13, 11:48am

[2] http://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2013/dec/24/atheism-richard-dawkins-challenge-beliefs-homeless

, accessed 12/28/13, 4:15pm

No comments:

Post a Comment