Readings from the Song:

Woman: 1:5-6 (don’t despise me because I am black)

Man: 4:9-16 (you are beautiful and you smell sexy)

Woman: 5:2-8 (ready for “bed” and can’t find lover)

Man: 7:1-9 (you’re beautiful, this time with food)

I joked with my students in describing this retreat

that it was going to be about the

sexy, sexy Bible. Was I kidding?

For centuries, we’ve tried to figure out this poem.

Some see it as a kind of performance

art,

reenacting a fertility rite to bring

good fortune to crops.

Others as an allegory

—a one-to-one metaphor for God’s love

for recalcitrant Israel.

It’s read on Passover in many Jewish

households because,

in the words of my friend Rabbi Yitz,

“Passover is the dating process

of the just-born Jewish nation with

G-d,

culminating in the Marriage Ceremony

under the canopy of Clouds at Mount

Sinai.”

For many Christians, it’s been God

dating the Church instead.

Others see it as a celebration of

physical and romantic love, God-given.

Still others wonder why it’s in our

Scriptures at all

—God’s not mentioned once.

Do we ever read it in church? Not

much.

And then only the least racy parts.

Like, not the bits with dripping nard

or channels or bellies

and breasts and lips.

That stuff is best kept far away from

Sunday morning.

Only, why? Are we embarrassed?

We are certainly embarrassing

as a Christian people

to non-Christians who don’t

understand why

we’re so embarrassed about our bodies

and what they do.

The Song of Songs is, at least a little bit, all these

things.

The woman who wrote the Song

and the men who included it in the

canon of scripture

and the millions of Jews and

Christians who have read it

across the centuries have already

voted.

This Song is scandalously specific

and ambiguous.

It is almost pornographic and deeply

spiritual.

The Song of Songs is about sustaining

relationships

and about constantly striving

and it is about the love which is the

ground of all our being

in one way or another.

First, it’s poetry. Some of your eyes are lighting up at the

thought,

others are bracing yourselves for a

long, boring lecture

and ultimately not understanding any

more than when you began.

Don’t worry, I only mean that it

means more than it seems to mean.

Like the TV show Lost. Or whatever

your favorite pop song is. Only better.

So, The Song of Songs is about a

woman

who is deeply in love and lust with

her beloved

who may or may not be King Solomon.

Probably not.

And they have frequent trysts but apparently don’t live together.

And they have frequent trysts but apparently don’t live together.

Or maybe they’re married,

though the text doesn’t offer much

support for that.

Or maybe their relationship is

scandalous somehow

since she gets beaten at one point

for trying to find him.

It’s not a straightforward story-poem

with a beginning, middle, and end,

nor is it entirely clear who the

characters are.

It reads a bit like a series of

monologues

between the man and the woman

but they don’t always flow from one

to another.

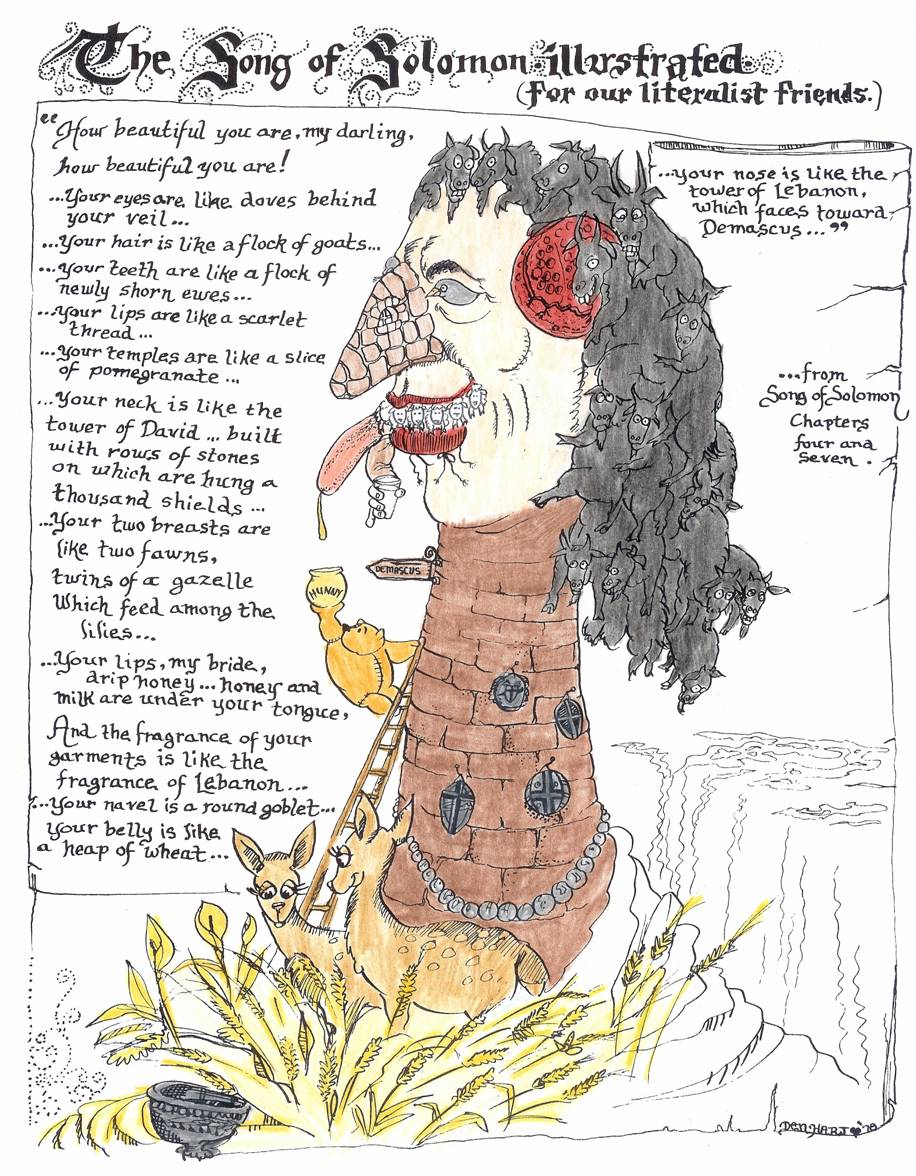

The language, as you might expect, is

heightened, is metaphorical;

“your teeth are like a flock of

goats,”

“your neck is like a tower, all it’s

stones in courses.”

It’s like saying, “your skin is as

soft as a kitten’s fur”

or “your hips are as curvaceous as

the Guggenheim Museum

and truly, they don’t lie.”

Her neck is not a tower, not really,

and her teeth aren’t hairy like a

flock of goats.

It’s about taking inspiration

from the natural and human-made world

—what’s beautiful to you?

That’s what you compare your love to.

“Your body,” she says in one place,

“is like ivory.”

Which, it turns out, is a lot like

other places in scripture

when someone sees someone else’s

“feet,” meaning genitals.

The Hebrew word translated “body”

means a man’s midsection,

so the woman is speaking of the man’s

penis as like ivory,

like an elephant’s tusk.

Yes, in a lovely, poetic way, she’s

saying,

“my beloved is well-hung.”[1]

Second, the Song of Songs is part of a theology called “Bridal

mysticism,”

the theology derived poetically

that Jesus is our collective and

individual boyfriend.

If you think of it literally, it’s a

bit creepy.

But also beautiful and has a long

history in the church.

We see married people all the time

—certainly we see broken marriages,

but also connectedness and reliance

and mutual giving.

Of course we’d use it as a metaphor

for our relationship with God.

Bridal mysticism takes Jesus as the

boyfriend to its logical extreme

and puts the mystic or the reader in

the place of the bride

—when we read these passages, when we

pray,

we can experience the great hope a

bride feels,

the anticipation of new life,

the excitement of being with the one

our heart most desires

—you know this feeling.

Not just the heart palpitations of a

crush,

but the deep connectedness to someone

we truly love

and who loves us back.

For some of you, that might be a romantic

or married partner,

for others it might be a deep

soulfriend,

for others it could be the

relationship you have

with a parent or sibling.

These are beautiful experiences and

we ought to want them—

but they require a certain

vulnerability on our end.

We have to be able to be vulnerable

to God.

Bridal mysticism requires us to

present ourselves

exactly as we are to our bridegroom

Jesus.

Third, and maybe most important,

“the protagonist in the Song is the only unmediated female

voice in scripture.”[2]

Meaning, every other woman’s story is

told by someone else,

either by another character in a

story or by the writer of the book.

Here, the woman speaks in the first

person,

she is a woman in touch with her own

heart and mind,

a woman in touch with her sensuality,

a woman empowered.

And so, because her story needs to be heard, I’ll tell it to

you,

at least, an imagined story of how

she came to write this poem.

I was told I had to work in my

brothers’ vineyards.

I was told I had dark, ugly, black

skin.

I was told I’d never amount to

anything, that I was unloveable.

I was told I would have babies and

that would make me valuable.

I was told to be quiet in church, to

submit to my husband, to lie back and think of England.

I was told it was all in my head,

that it was my fault.

I was told.

And now I will tell.

When I saw him the first time, I came

over all giddy.

I was talking to my friend and

suddenly I was stammering

and my hands were shaking and my nipples

were hard

and I couldn’t stop staring.

When he talked to me the first time,

I looked down at my shaking knees,

knowing he couldn’t possibly find me

pleasant to look at,

but he lifted my chin with a finger

and looked at me

like no one else ever had.

He really saw me—what did he see?

He said that I was more beautiful

than a flock of goats on the hillside,

more sweet than persimmons dipped in

honey,

more elegant the Temple Mount itself.

He said, “she’s a brick house!”

He compared my breasts to round baby

sheep

nursing at their mother’s side.

He said my heart was bigger than the

Jerusalem marketplace,

that my mind was sharper than the

rocks at the shore

which tear up the hulls of boats,

that my ass was as round as melons

and how he wanted to take a bite.

How could he see this when I am, at

best, average?

He saw me and he loved me.

And I saw him and I loved him.

We devour each other with our eyes.

When we see each other around town,

from yards and yards away,

we cannot resist seeing, we cannot

resist knowing.

I know that last night we spoke of

philosophy and the nature of God,

we spoke of politics and farming and

birds and bees,

we spoke of our fears and of our

darkest fantasies.

And we touched each other

—we removed each other’s clothes

slowly, achingly slowly,

fingers tracing the hollow of the

throat,

like the curve of a spoon dipped in

custard,

fingers circling wrists vulnerable as

newborn puppies,

fingers caressing inner thighs,

open like a book revealing its

secrets.

And today, when we see each other,

we know, deeply, what the other looks

like under their clothes,

how they respond to kisses and

challenges.

We devour each other with more than

our eyes.

Yet I cannot see him now.

And so often, I cannot find him.

He doesn’t respond when I text and

our friends have not seen him.

I run across sidewalks and fields,

through the autumn trees smelling of

wet leaves and death

and I weep.

I meet people as I wander and they

look at me in disgust.

They speak harshly, telling me no one

could love me as he does,

telling me I’m making a fool of

myself,

telling me to not to speak up for

myself,

telling me to go home.

And so I return to my bed, to my

empty apartment

which still smells of his soap and

his skin and sex.

I return to my shower and wash away

my tears in hot water.

I rub lotion into my skin and put on

my pajamas,

giving in to exhaustion.

I tell myself it will be better

tomorrow.

I tell myself he will return.

I tell myself to fall asleep.

I give in memories and touch myself.

And just on the edge of sleep, I

think I hear him next to me,

his hand on my belly, his lips at my

ear.

I wake with a jolt but he is not

here.

I run to the door,

my hands still slick with lotion and

my own moisture,

my feet bare,

but he is not there.

And later we have carved out time to

lie on the grass,

feeling the warm sun on our skin,

seeing the red glow of it through our

eyelids,

smelling burning leaves and each

other’s familiar scent.

Cloves and eucalypus and nard filling

my nose and my heart.

His hand in mine, our only

touchpoint, yet containing multitudes.

I bask in my beloved’s presence and

he in mine.

And tell him,

Many haters cannot quench your love

for me.

Many insults will not quench my joy

in my own body

nor the want I feel for you, my

beloved.

Many sorrows and arguments will not

quench our commitment.

Many wars cannot quench the spark of

the divine and the hope of peace.

Many waters cannot quench the fire of

my love,

neither can floods drown it.

For the holiness of all that is love,

hear me tell you my story and know this same love.

[1] http://www.relevantmagazine.com/life/what-bleep-does-bible-say-about-profanity#DSeOAuW9zxew2TM4.99

Accessed 1:06 pm, 10/2/14

[2] Women’s Bible Commentary, “Song of

Songs” by Renita J Weems, 164